The Keening Tradition

Keening was a vocal ritual artform, performed at the wake or graveside in mourning of the dead. Keens are said to have contained raw unearthly emotion, spontaneous word, repeated motifs, crying and elements of song.

The word keening originates from the Gaelic caoineadh meaning “crying”. The keening women (mnàthan-tuirim), paid respects to the deceased and expressed grief on behalf of the bereaved family.

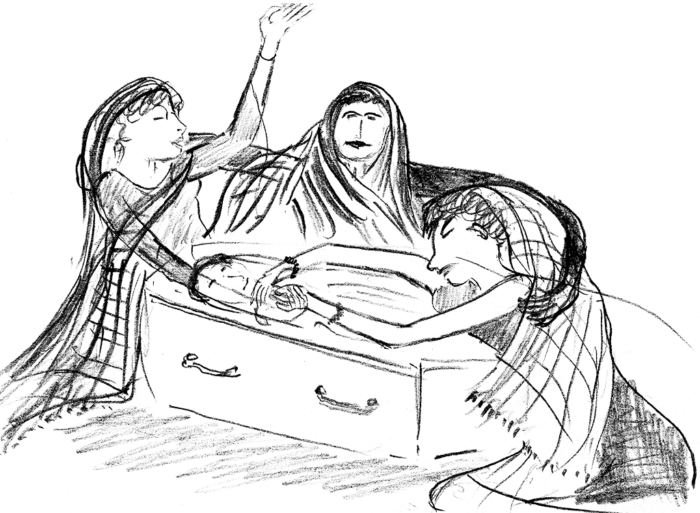

Keening was an integral part of the whole process of undertaking and was performed either at the wake, funeral procession or interment. It was a skilled ritual artform at the meeting point between life and death, and received due respect, including payment. Keeners were generally experienced elder women. Many believed the act of keening enabled the deceased soul to leave the body, and that keening was required, thus giving the role huge importance.

Although the last known keens took place in the first half of the twentieth century Ireland and in the ninetienth century in Scotland, the social practice of keening will have influence in people, places and voices we (and they) can never know. Amongst the travelling people one of the highest compliments to a singer today would still be to recognise the voice of the keener in her.

A keen is distinct from a lament. The Colin’s English Dictionary defines a lament as ‘a poem, song, or piece of music, which expresses sorrow that someone has died’. There is a vast store of heart rendering laments that can be played or sung at any time and in any place in remembrance. However a keen is the final farewell to the deceased, and was composed and performed live, often touching the coffin and addressing the corpse. There would usually be three or more women that were cultural professionals. It was only towards the end of the tradition that you would find a singular woman performing a keen.